This paper work is a continuation from the previous post: Introduction of Urban Planning: Urban Design Methods and Theories [Writing for Master Course, 2007], an assignment submitted for the Master study course Urban Design Methods and Theories of the Department of Urbanism, Faculty of Architecture, Delft University of Technology (TU Delft). This writing is not the full version of the assignment, only one case study are showed.

Borneo Sporenburg

Context

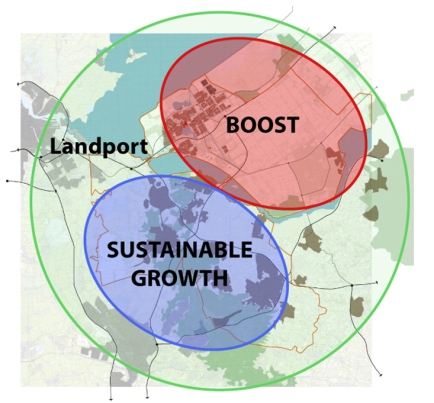

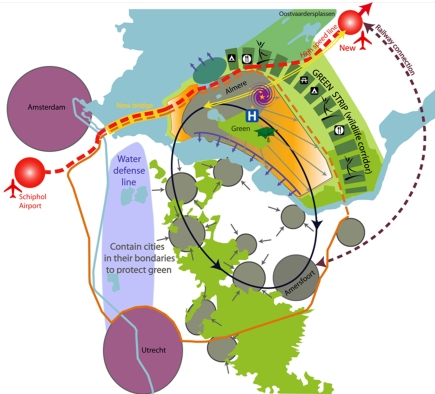

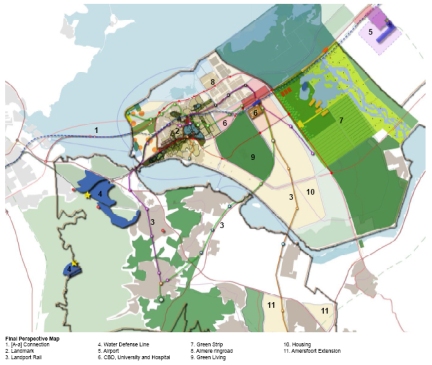

In 1996, West 8 was commissioned to transform Borneo and Sporenburg, two expansive massive docks on Amsterdam’s eastern waterfront, into residential neighborhoods with 2,500 housing units. The program called for suburban-style, low-rise housing, each with a front door opening onto the street, to be introduced into a high-density urban setting with 100 units per hectare (roughly 2.5 acres), three times the density of a typical suburban development.

|

| Borneo Sporenburg Area View |

Actions and Achievements

Low-rise structures are arranged into strict banded blocks and sub-divided into individual parcels, each containing an inside void that comprises 30 to 50 percent of the parcel. More than 100 architects participated in the planning process, developing new housing prototypes that incorporate these voids. The resulting designs include patios, roof gardens, and striking views of the waterfront. The Borneo Sporenburg plan divides the grid of low-rise buildings in three zones with architecturally distinctive high-rise residential buildings, or “sculptural blocks,” which create significant landmarks within the harbor landscape. These sculptural blocks, informally known as the Sphinx, PacMan, and Fountainhead, also contain collective open spaces in the forms of courtyards or gardens. The water surrounding the docks serves as the dominant public space, open to Amsterdam’s boating culture.

|

| The Area before intervention |

Committed to creating unique structures within a unified whole, West 8 worked closely with the architects who designed the various structures including O.M.A., Neutelings Riedijk, Mastenbroek, Miralles, van Berkel en Bos, and Mateo. West 8 designed the gardens and other open spaces, as well as such landscape elements as the three sculptural bridges that connect the different neighborhoods on the peninsulas, each sculptural in appearance. Borneo-Sporenburg was completed in 2000.

|

| Borneo Sporenburg Program |

|

| Low Bridge and High Bridge designed by West 8 |

The low-rise bars of rowhouses are broken with large housing blocks shifted at a diagonal to the streets. Geuze talks of this new housing type—high density but low rise—as a way to attract developers, satisfying the market’s need for a high number of units per acre and the consumer’s desire for a hybrid between a mid-rise apartment and a single-family detached home of the suburbs. The complex mixes social housing with market rate; some is for people with special needs, young families, single mothers, the elderly, and those needing psychiatric care. Sixty lots were sold as individual home sites and developed by the people who would live there, rather than by speculators. Costs were often defrayed by splitting the units, most often nesting one family’s unit with another. Various architects developed sections (a hybrid dream of the heroic Marseille block and the current Dutch vogue for an ambiguous—sinuous, continuous, intricate—interpretation of spaces). The variety of facades and materials, along with the interpenetration of schools, provide breaks in what could be viewed (especially in the United States) as an insistent linearity and repetitiveness.

|

| Free Parcels and Quays challenging architects and clients |

Even in this project there was the difficulty of bringing in “outside” architects (stars), and several of the architects who were initially hired found it difficult to work with a public client. The inevitable starts and stops of funding and the approvals process take their toll. As master planner, Geuze says that he worked hard to get a varied array of architects involved, believing that it was worth the effort and political capital. There had to be faith in the designers and in the unfamiliar, though bureaucracies are by nature risk-averse, which often restricts the ability of a project to adjust, redirect, and innovate—to make the leap that is required in moving forward.

|

| Row Houses along the Waterside |

The project is not without shortcomings. (Though it is the overwhelming success of Borneo Sporenburg and its planning that opens it to this closer scrutiny.) For instance, there is little commercial and retail development interspersed with the housing—the outcome of an agreement with the anchor commercial tenant at the edge of the housing. No small stores commingle on the blocks, requiring long walks for necessities. (even the original Levittown had small commercial centers, for the one-car families.) The public spaces seem less considered, though streets are carefully made and do refer back to an earlier Dutch type. The lack of relief in the form of mature green spaces and trees lends a sere quality to the surrounding landscape in its initial years.

Unlike the traditional model in which the developer is in the lead, here the design team devises the scheme, which is then presented to the municipality. The municipality agrees on a blueprint of its own, an overarching set of goals for physical planning. It then finds developers who will work within the broad guidelines established by the winning team of architects, landscape architects, and planners. This process differs fundamentally from most development work in the United States. It is not the developers’ fault; the public good is, literally, not their responbility. It is, however, the responsibility of civic government.

|

| Sphinx; architect: Frits van Dongen |

In the Borneo project, there was clearly the needed professional expertise “in house”: designers who worked for the city could evaluate design proposals. This responsibility has not been “outsourced” or relinquished. In contrast, we often find U.S. housing authorities with no professional design staff; they have ceded that responsibility to the development community and have gotten out of the business of participating actively in the design of public services. At this juncture, the erosion of rights for all citizens can occur. The city is, after all, our collective public space.

|

| Sphinx Garden; architect: Frits van Dongen |

Work such as this does not happen of its own accord. It is nurtured by support, in this case almost entirely public. Designers are commissioned to undertake public work and given the means and time to do that work. Most important, they are brought in at the beginning of the process. There is the confidence that design is not decoration, but fundamental to the rethinking of public institutions and public space. Not only are funds made available but governmental agencies actively engage emerging designers, allowing them to develop international opportunities and alliances through work on Dutch consulates overseas,. Architecture, landscape architecture, and industrial design are seen as viable exports, and ambassadors abroad.

The success of the Borneo project underscores the difficulties of making new sections of the city that are complex but conceived at one point in time. Leaving unassigned space for the incidental, accidental, spontaneous, and often fleeting colonization makes a city real.

|

| Fountainhead; architect: Kees Christiaanse |

Back in the historic center, walking to the hotel past the large framed by the great arched passageway of the Rijksmuseum, it is not the cleverness of the landscape design or the monumental gothic revival facades that are striking (though these all contribute to the impression), but the density of activity filling the space and surrounding streets—people lying on the grass, walking, eating and biking. It is a full-color version of a contemporary city in motion. In an abstract field of angles and points, cars, trams, and people make a grand prospect of a civil society out in public.

Delft, January 2007

Sigit Kusumawijaya

Urban Design Methods and Theories: Introduction of Urban Planning

Writer: Sigit Kusumawijaya

Supervisor: Ir. Willem Hermans

Status: assignment submitted for the Master study course Urban Design Methods and Theories of the Department of Urbanism, Faculty of Architecture, Delft University of Technology (TU Delft)

Year: 2007

Writer: Sigit Kusumawijaya

Supervisor: Ir. Willem Hermans

Status: assignment submitted for the Master study course Urban Design Methods and Theories of the Department of Urbanism, Faculty of Architecture, Delft University of Technology (TU Delft)

Year: 2007